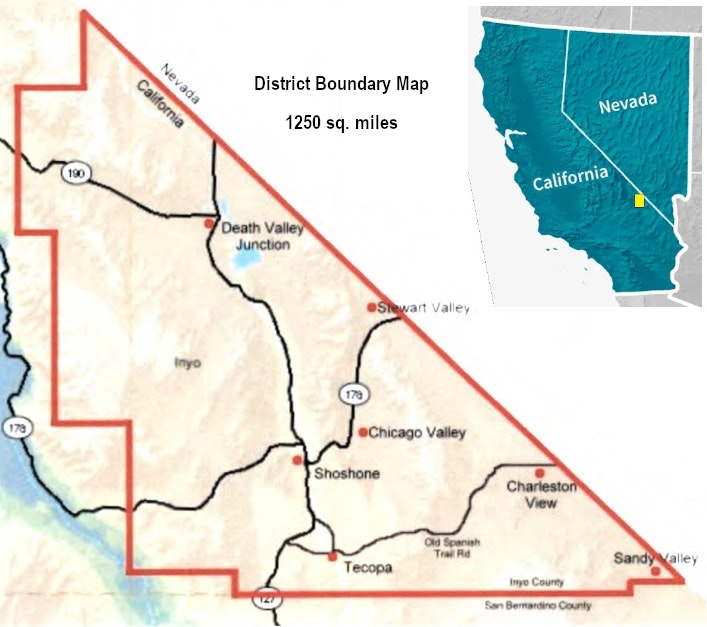

In Southern Inyo County, California, even the most basic lifeline of emergency response has begun to fray. For months, the district’s radios—its only reliable way to summon volunteer firefighters and EMT across 1,200 square miles—have been effectively dead.

At the Nov. 20 board meeting of the Southern Inyo Fire Protection District (SIFPD), Fire Chief Bill Lutze tried to keep the mood light: “We send up smoke signals now,” he said with a weary smile. In reality, firefighters have been coordinating calls in an area without cellular coverage through WhatsApp and personal phones because the Ibex Pass repeater has stopped paging volunteers, forcing the district to relocate it to nearby Shoshone simply to try to restore minimal coverage.

The image of firefighters piecing together a communications system by hand is more than an anecdote. It is the portrait of a rural district confronting a convergence of pressures: a thin volunteer roster, aging equipment, rising call loads, and—on the horizon—a 500-megawatt industrial construction project in Charleston View that would instantly reshape the region’s emergency-response landscape.

Reviving a Decade of Industrial Energy Plans in the Desert

SIFPD received its first formal notice of a major industrial project on May 6, 2024, when a letter arrived at the district’s Tecopa post office box. Signed by Senior Project Manager Jack Dangelo of Energy Project Solutions, the correspondence introduced Bonanza Peak Solar, LLC, a subsidiary of national solar developer 174 Power Global, which is in turn a subsidiary of Hanwha Group.

Described on Wikipedia as “a large business conglomerate (chaebol) in South Korea,” Hanwha was, “Founded in 1952 as Korea Explosives Co. [and] has grown into a large multi-profile business conglomerate, with diversified holdings stretching from explosives—their original business—to energy, materials, aerospace, mechatronics, finance, retail, and lifestyle services.”

The letter from Energy Project Solutions outlined the early details of a proposed up to 500-megawatt photovoltaic power plant planned for the outskirts of neighboring Charleston View.

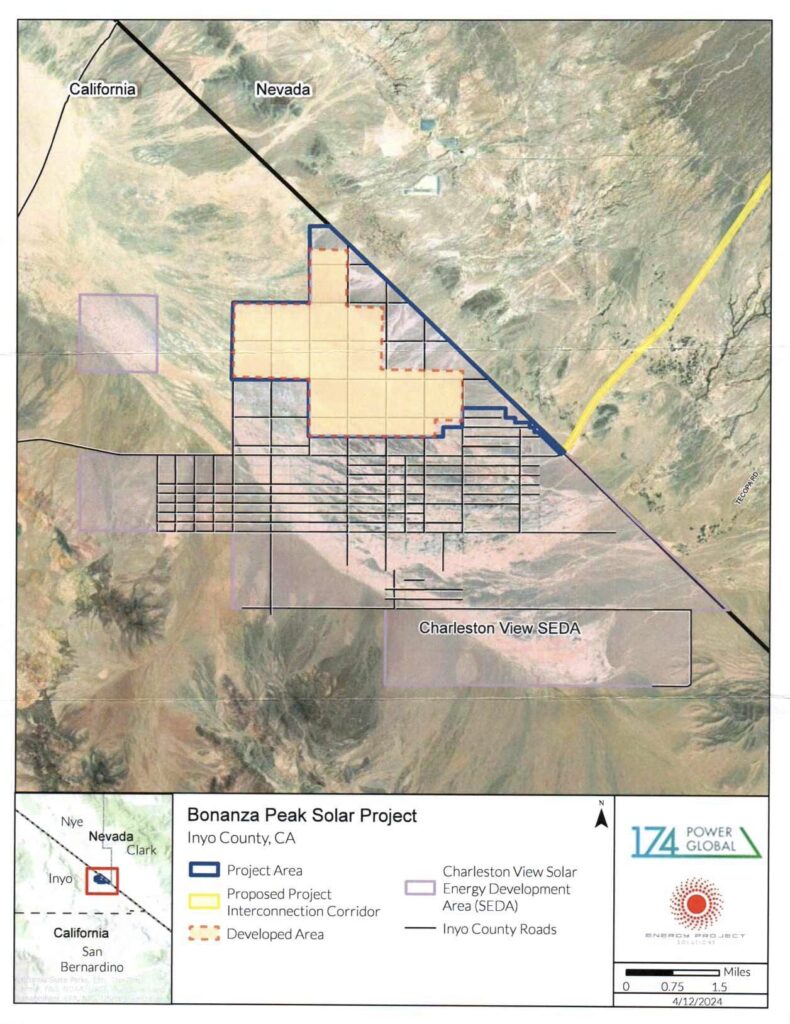

The developer framed the outreach as the beginning of a “pre-permitting” phase with Inyo County, offering to meet with fire district leadership and requesting a point of contact to coordinate future information. The letter was accompanied by a two-page fact sheet and a map showing the sweeping footprint of the project: approximately 2,400 acres of private land just north of Old Spanish Trail Highway, aka Tecopa Road, abutting the Nevada state line. The plan includes solar arrays on single-axis trackers, an on-site substation, operations facilities, and—at least at the time of the letter—a battery energy storage system.

Construction, according to the documents, could begin as soon as the second quarter of 2027 and continue for 16 to 18 months, signaling one of the largest modern construction mobilizations the southeast corner of Inyo County has ever seen.

The location is not incidental. The proposed project lies entirely within the Charleston View Solar Energy Development Area (SEDA), a special planning overlay established by Inyo County more than a decade ago to concentrate industrial solar development within a specific portion of the Amargosa Basin. County officials created the SEDA after earlier waves of solar speculation—involving projects such as Hidden Hills and Sandy Valley—raised concerns about groundwater depletion, wildlife impacts, and piecemeal development creeping across fragile desert habitats. The SEDA was intended as a compromise: a concentrated zone where large-scale renewable projects could proceed with clearer rules and reduced conflict.

For developers, the SEDA offers predictable zoning and proximity to Nevada’s grid infrastructure. For over a decade, Charleston View—an unincorporated, sparsely populated area long caught between California and Nevada planning regimes—has lived with the promise, and the threat, of becoming an industrial energy hub.

Bonanza Peak Solar is the latest and largest in this lineage. While previous concepts stalled, scaled back, or were withdrawn under scrutiny, 174 Power Global’s proposal represents one of the most concrete moves toward actually developing the SEDA at utility scale. The company’s materials emphasize environmental compliance, minimal groundwater use, and traffic controls intended to mitigate construction impacts. But for local agencies such as SIFPD, the notice raises immediate questions about emergency response, staffing, and infrastructure during a high-intensity construction period.

A Rural District Braces for a 450-Worker Construction Zone

Charleston View has an official population of 45, making it the 1561st most populous place in California based on the U.S. Census.

The Bonanza Peak Solar Project, which briefed both the Inyo County Board of Supervisors and SIFPD on Nov. 4, is expected to bring approximately 450 workers into Charleston View for their buildout—ten times the residential population and the largest single work site Inyo County has seen in modern memory. Representatives from developer 174 Power Global confirmed those numbers during the Board meeting.

In a recent letter responding to 174 Power Global, SIFPD warned that the project will “entail a significant increase in demand on SIFPD’s services,” pointing to OSHA construction-sector injury rates—2.4 non-fatal injuries per 100 workers per year—which equate to roughly 10–11 injuries annually for a 450-person workforce. Over the full construction period, that means about 16 projected onsite injuries, even before accounting for collisions, heat emergencies, roadside incidents, or the compounded hazards of a remote industrial zone.

For a district with only one active EMT—who receives $45 per call—the arithmetic is stark. With just one additional volunteer onboard that recently passed necessary licensing exams and another only “in the early stages of the hiring process,” even baseline injury projections would mark a dramatic increase in workload. The question now is whether SIFPD can secure the resources it needs to scale up before construction begins.

For years, SIFPD volunteers have responded out of commitment to neighbors—not corporate contractors. And the board is increasingly explicit that this distinction matters. In its letter to 174 Power Global, the district wrote that while volunteers “love our community and feel a calling to serve their neighbors,” they cannot be expected to absorb the medical and safety risks of a construction project for a for-profit developer without compensation.

“In recognition that our volunteers would be responding to emergencies at Bonanza Peak Solar for a for-profit company that isn’t from our community, we will be requesting reimbursement… for increased volunteer call-out pay,” the district wrote to the developer.

Two New Fire Stations Shift From Aspirational to Essential

As Bonanza Peak advances, SIFPD is simultaneously attempting the most ambitious infrastructure expansion in its history: constructing two new fire stations—one in Tecopa Heights and one in Charleston View.

According to the 2020 census, Tecopa’s population is 120, but that number swells in the winter months as snowbirds descend on the area’s popular hot springs. The district’s primary station is located in Tecopa Hot Springs, the center of the area’s tourism activity. Located on BLM land adjacent to Tecopa’s community water kiosk—another purview of the SIFPD—the new Tecopa Heights substation would finally give the most densely residential part of Tecopa a dedicated response base.

On October 13 the importance of the new location became clear: the future substation was yards from the scene of a fire that engulfed a handful of recreational vehicles, quickly jumping from one property to the next. SIFPD responded alongside neighbors with little training in firefighter safety, working together to save a row of homes along Bob White Way from going up in flames. No injuries were reported.

Firefighters were dispatched at 5:30pm, working until 1:30am to extinguish the fires. According to SIFPD’s press release: “Due to the strong and gusty winds, and along with neighboring structures being threatened mutual aid was requested from Pahrump Valley Fire and Armargosa Fire who responded and arrived on the scene.”

Another substation would be built in Charleston View, 23 miles away from Tecopa Heights, at a far more complicated location. The parcel earmarked for SIFPD by Inyo County lies squarely within a floodplain. Building there would require elevating the site at extraordinary cost—potentially consuming the district’s entire capital budget before a single wall could be raised. SIFPD is now seeking a better parcel.

For Charleston View residents, a local station isn’t just operational convenience—it’s transformational. The community currently exists in an infrastructure limbo: long response times, high-risk insurance classifications, and a lack of conventional mortgage access. A fire station could stabilize insurance rates, open access to financing, and increase the long-term value of properties that have struggled under the burden of uninsurability.

A Fire Protection District Is Not a City Department

In California, a Fire Protection District is a stand-alone government—not a city department with salaried staff and a general fund. A district like SIFPD must build its entire financial base from scratch: levying special tax assessments, applying for competitive grants, and scraping together donations to maintain engines that are often older than the volunteers driving them.

The district depends on people, not payroll. Volunteers—many with full-time jobs—are the backbone of a response network covering one of the largest service areas of any volunteer fire district in the state. Basic infrastructure for a municipal fire company—functioning radios, staffed stations, and response redundancy—becomes a continual challenge in a district that survives year-to-year on modest assessments, fundraisers and small grants.

This is the context in which a 500-megawatt industrial project arrives.

Financial Reality: A Budget Not Built for Industrial-Scale Risk

A six-year review of the Southern Inyo Emergency Response fund shows a district increasingly constrained by costs it can no longer control. While annual revenue has hovered between $118,000 and $129,000, the expenses required to keep SIFPD operational have grown steadily—and in several cases, sharply—pushing the district toward a projected –$32,589.95 deficit by FY 2025–26.

One of the clearest examples is insurance. In 2021, the district paid $6,249 for liability and vehicle coverage. Today that figure exceeds $21,000, a more than threefold increase that reflects both statewide market pressures and the district’s exposure across a 1,200-square-mile service area. Insurance is now one of SIFPD’s largest recurring expenses.

Maintenance costs tell a similar story. The district’s aging engines and equipment have produced increasingly volatile repair bills, with the Maintenance of Equipment—Materials line item rising from modest amounts early in the period to nearly $9,000 in 2024. Those spikes are compounded by state-mandated pump tests, parts availability challenges, and the district’s reliance on older apparatus that are expensive to retain and impossible to replace without outside funding.

Even everyday operating costs have climbed in ways that strain the district’s limited budget. General operating expenses—a category that includes fuel, firefighting consumables, utilities, radio program costs, and unclassified operational needs—rose from $7,033 in 2021 to more than $28,000 in 2024, quadrupling in three years. That surge corresponds with the period when the district’s repeater system began to fail, forcing ad-hoc communication fixes and increased travel for equipment troubleshooting.

Professional and special services—legal compliance, payroll processing for stipended volunteers, accounting, and other contracted support—have also increased, rising from roughly $1,500 in 2021 to $3,690 so far in FY 2026. These expenses reflect the administrative burden placed on even the smallest special districts: annual audits, federal reporting requirements, and regulatory compliance that cannot be deferred.

Taken together, these pressures form a pattern. The district’s Services and Supplies category, which captures most day-to-day operational costs, nearly doubled between 2021 ($31,426) and 2024 ($61,070). Revenue did not follow. SIFPD now spends more simply to maintain baseline readiness than it did to operate the entire district several years ago.

This is the fiscal backdrop against which the Bonanza Peak Solar Project arrives. Even without an industrial-scale construction zone, SIFPD is struggling to keep pace with inflation, equipment aging, and regulatory requirements that grow more expensive each year. With the project projected to bring hundreds of workers and a significant increase in emergency demand, the district’s structural deficit is no longer an abstract concern—it is a direct threat to its ability to respond.

SIFPD holds $229,620 in unrestricted reserves across its accounts—a sum that must cover everything from fuel to station construction start-up costs. While it looks healthy on paper, it is dwarfed by the district’s capital obligations.

At the Sept. 18 board meeting, SIFPD Treasurer Colette Zelwer stressed that the district cannot ask voters to approve a new special tax in 2026 until it has a clear capital plan: “We need to know how much the new fire stations will cost to build and maintain.”

SIFPD has secured $1.5 million in federal appropriations through the district’s representative in congress, Kevin Kiley, and $500,000 in matching grants from Inyo County to build the new stations in Tecopa Heights and Charleston View. Once they sign on the dotted line, SIFPD has five years to build. But the district warns the funding is insufficient, given inflation, construction costs, and Southeast Inyo’s remoteness. Additional support from Bonanza Peak—especially for Charleston View—is essential.

Projected Call Volume Surge Under Bonanza Peak

Historically, SIFPD handles roughly 50–60 calls per year—a number reflected in recruitment materials and internal logs. But this baseline is unlikely to hold during an 18-month construction cycle.

At the Nov. 20 SIFPD board meeting, Chief Lutze also cautioned that OSHA’s injury projections understate the true burden. Construction brings its own hazards: collisions with heavy trucks, heat emergencies, equipment failures, and remote-area rescues that federal formulas don’t capture.

Even a modest increase could push SIFPD into the 70–90 calls per year range during construction. For a district currently relying on one EMT and volunteer labor, this is not a manageable adjustment—it is a structural shock.

Fractured Emergency Data Reveals Deeper System Dysfunction

As SIFPD confronts these pressures, another issue has surfaced: seemingly nobody has a complete dataset of Southeast Inyo’s emergency activity. And that gap is now part of the public-safety story.

Chief Lutze provided SIFPD’s internal call totals for the last three operational years, showing between 60 and 64 fire and EMS responses annually—including all incidents, even when dispatch systems failed.

But when the Inyo County Sheriff’s Office produced dispatch records for the same region, the dataset was drastically thinner: just 42 fire/medical calls. Several known incidents—including a Feb. 11, 2025 fire at Borehole Spring, the largest of the season—were missing.

“If dispatch gets a call of a man down, a [Sheriff’s Officer] unit will respond then request us. In that case it will show as a S/O call not a fire/ambulance call,” Chief Lutze emailed TecopaCabana. Adding, the county data “may not capture all responses other than if they receive a direct call for ambulance/fire for us.”

A comparison of SIFPD’s internal records with the county’s dispatch logs shows how profoundly incomplete Inyo County’s emergency dataset is. Over the last three operational years, the district logged 186 total fire and EMS calls, while the county dataset recorded only 63 for the same periods—an undercount of nearly two-thirds.

Total calls within each SIFPD operational year:

| SIFPD Year | SIFPD Total Calls | County-Recorded Calls | Gap |

| 2022–2023 | 64 | 19 | –45 |

| 2023–2024 | 62 | 24 | –38 |

| 2024–2025 | 60 | 24 | –36 |

For a district already strained by rising call loads, the absence of accurate regional data has real consequences: it weakens grant applications, complicates long-term planning, and undermines SIFPD’s negotiating position as the Bonanza Peak Solar Project moves toward necessary approvals.

“When we receive a call it is put into our run sheet by hand for the date, location, unit numbers that responded and the id number of the personnel responding and if it’s a full response, canceled or standby,” wrote Lutze, who kindly took the time to compile paper records for this article.

A closer look revealed why the discrepancies exist:

- The Sheriff’s search was filtered only by three call signs (2700, 2701, S70).

- Incidents involving other responders (TSVFD, mutual-aid departments, federal agencies, Nye County units) never appeared.

- The search was restricted to beats 600 and 700, map zones that don’t cleanly cover Southeast Inyo communities.

This fragmented landscape means:

- State agencies receive incomplete risk data.

- Funding formulas skew against rural districts.

- County emergency planning is built on partial visibility.

Amid these discrepancies, Inyo County recently secured a $67,000 from California’s Office of Traffic Safety (OTS) Traffic Records Improvement Grant—a modernization effort explicitly designed to purchase digital equipment for officers to better record data, with the goal of fixing inconsistent reporting, delayed data, and gaps between agencies. The grant will upgrade e-citation and crash reporting and connect county data to statewide systems like the California Highway Patrol-managed Statewide Integrated Traffic Records System (SWITRS) database.

But while the OTS grant targets traffic records, the structural issues mirror SIFPD’s challenges: outdated tools, fragmented systems, and missing information in a region with a proposed national monument, rising tourism and growing development pressure.

For now, the people responding to emergencies know how busy they are. The public datasets meant to reflect that reality do not.

“I’m confident that our call sheets reflect our calls,” Lutze went on, “whereas dispatch may not capture the calls because they can be mixed with other incidents they are working.”

Traffic Hazards Add Another Layer of Risk

Traffic may become one of the district’s most persistent challenges during the solar project construction period. Old Spanish Trail Highway—a narrow, deteriorated, shoulderless rural corridor used mainly by oversized vehicles destined for nearby off-highway vehicle (OHV) recreation area Dumont Dunes—is expected to see over a year of sustained heavy-truck traffic coming across the California-Nevada border from Las Vegas.

District officials have warned that deteriorating pavement, tight turns, and limited visibility could elevate crash risks and slow emergency response during peak construction activity.

These concerns are amplified by what statewide traffic data already shows. According to the California Office of Traffic Safety, Inyo County recorded 84 injury or fatal collisions in 2022, the most recent data year available, including multiple crashes involving unsafe speed, roadway departures, and rural-road visibility issues. OTS has consistently noted that rural counties—especially those with incomplete reporting—tend to undercount true collision rates.

The anticipated increase in heavy-truck use on Old Spanish Trail Highway, layered on top of the county’s 2022 collision data, heightens the urgency of improving both roadway safety and traffic-incident reporting.

California Highway Patrol (CHP) crash data for 2025 shows that Old Spanish Trail Highway—SIFPD’s most remote and least forgiving corridor—continues to generate a disproportionate share of collisions in southeast Inyo, despite its sparse population and wide-open desert setting. Nearly every incident along the route falls under CHP Beat 052, the same rural patrol area now bracing for the influx of heavy construction traffic tied to the Bonanza Peak Solar Project.

The CHP Inland Division’s website describes how officers there “face the widest spectrum of traffic enforcement challenges of the CHP’s field Divisions. Officers patrol an area larger than 12 individual states. Included in the geographical boundaries are the lowest point in the United States at Death Valley, and the highest point in the contiguous 48 states at Mt. Whitney.”

The crash narratives paint a consistent picture: nighttime collisions on unlit stretches, single-vehicle rollovers, loss of control on long desert straightaways, and abrupt maneuvers triggered by wildlife or poor visibility. Several incidents cluster in the undulating curves outside Charleston View, where blind rises and narrow shoulders have created a long-standing hazard for both locals and tourists. The timing of these collisions—early morning, late night, and everything in between—underscores that risk is not seasonal or incidental; it is structural.

Old Spanish Trail Highway is primarily a county road, not a state highway. That places responsibility for safety improvements, signage, lighting, and grading squarely on Inyo County, which already struggles with limited road-maintenance staffing and a backlog of deferred infrastructure work. As SIFPD leadership warns about the district’s ability to keep pace with emergency demand, the county faces its own parallel challenge: maintaining one of the region’s most accident-prone travel corridors as industrial development accelerates around it.

The data also reveals another critical blind spot in the way rural emergencies are documented. Many Old Spanish Trail Highway crashes never generate a fire or EMS response and therefore never appear in SIFPD’s internal logs. Others show up in CHP’s statewide database only when an officer completes a full SWITRS report—leaving significant gaps between what the Sheriff’s Office, CHP, and the fire district each record. This fragmented reporting system helps explain why SIFPD’s call numbers differ so sharply from the dispatcher summaries provided by the county. And it has practical consequences: incomplete datasets weaken the district’s and the county’s negotiating position when seeking traffic-safety grants or community-benefit agreements from large renewable-energy developers.

It is also why Inyo County’s recently awarded OTS grant matters so deeply here: without accurate, real-time traffic data, state agencies cannot accurately assess or fund the risks facing communities like Charleston View.

What Bonanza Peak Has Offered—and What SIFPD Still Needs

Even as discussions around Bonanza Peak intensify, the project itself remains at a very early stage in the county’s approval process. Inyo County has just begun its CEQA environmental review, the mandatory process that includes impact studies, tribal consultation, and public comment. Until that analysis is completed—likely sometime in the spring of 2026 according to the Inyo County Planning Department—the project cannot begin the permitting process. In practical terms, Bonanza Peak remains at the very start of the county’s review process, with major procedural steps still ahead.

In addition to CEQA, the developer must secure a series of separate approvals before the project can reach the Board of Supervisors for approval. That includes authorization for use of the SEDA itself, permits for the facilities planned within the SEDA, and any temporary use permits necessary to cover the construction phase. The developer will also need to negotiate and finalize a community benefits agreement with Inyo County. Until each of these pieces is completed and approved, the project cannot move forward to a final vote.

Even so, if the developer clears all of the required approvals, the project is tentatively slated to begin construction in the second quarter of 2027. At the Nov. 4 Inyo County Board of Supervisors meeting in Tecopa, Bonanza Peak representatives emphasized they want to be responsive: removing the proposed battery-energy storage system after residents raised fire concerns; offering a better land parcel and some financial assistance for a Charleston View station; and expressing openness to negotiated benefits through the county’s development-agreement process.

But SIFPD’s needs far exceed what the developer has proposed so far. In its letter to the solar developer, the district outlines a multi-million-dollar package required to keep the community safe during construction:

- Financial support for construction of the Charleston View fire station, up to $1,000,000.

- Facilitating a donation of appropriate land for the Charleston View fire station.

Purchasing essential equipment at a total of roughly $1,000,000, including:

- 2x 2000-gallon Water Tender fire truck w/poly or stainless tank ($150k)

- 2x Type 4 fire engine with foam dispenser and 750-1000 gallon tank ($225k)

- Ambulance ($150k)

- 4x SCBAs [self-contained breathing apparatus] w/ 6x 45-minute tanks ($10k)

- Portable light plant ($30k)

- Tower at fire station for repeater and warning siren ($20k)

- Jaws of life ($10k)

- Ongoing financial support for SIFPD staffing and operations ($200,000/year).

- Triple call-out pay for volunteers responding to Bonanza Peak Solar incidents (as needed, ~$1k per incident).

Timing is everything. At the Oct. 16 SIFPD board meeting, the district’s appointed negotiator, environmentalist Patrick Donnelly, underscored that once the project is permitted by Inyo County, SIFPD’s leverage evaporates.

“They have a lot of money,” Donnelly told the board. “Don’t get dissuaded by any poverty claims.”

The strategy is clear: if SIFPD cannot secure commitments now, the financial burden of safeguarding the community will fall not on the corporation building the plant, but on a volunteer district, already operating beyond capacity.

A District at a Crossroads

The next several weeks will reveal whether the district can bring its operations and outreach in line with the demands ahead.

This fall, SIFPD approved new recruitment language aimed at strengthening its volunteer base—materials that now appear on the district’s website but not on its Facebook page, the platform where most residents actually follow district updates. It’s a small gap, but emblematic of uneven communication at a moment when even its primary radio system remains offline.

According to the recruitment materials, volunteers “face high-stress situations, sometimes working long hours in extreme conditions.”

Meanwhile, community fundraising remains one of SIFPD’s few flexible resources. Earlier this year, Inyo County awarded the district a small grant to support local fundraising efforts. Community Project Sponsorship Program (CPSP)—Inyo County’s grant program for local events and projects that benefit residents and attract visitors—has been an important catalyst for SIFPD, providing seed funding that helped the district kickstart its recent fundraising efforts and expand its community presence. That support enabled volunteers to cover upfront costs, promote events, and build momentum at a time when the district’s operating budget leaves little room for outreach.

With that support, SIFPD organized a flea market alongside the popular annual Tecopa Takeover festival in November, drawing visitors across Tecopa Hot Springs Road to the local community center where they raised $6,200—a meaningful sum for a district operating on roughly $120,000 a year, but also about $10,000 less than the previous year’s efforts. The proceeds now help cover operational needs that continue to outpace the district’s budget.

With the next CPSP funding deadline once again approaching on December 10 for projects taking place in 2026, SIFPD is expected to apply again for funding up to $7,500 to sustain and strengthen its community engagement and fundraising foundation.

On December 17, SIFPD will host a free holiday dinner for residents at The Flower Building in nearby Shoshone, with local restaurants providing meals financed through the remaining grant-supported funds. A silent auction, SIFPD merch sales and the popular annual handmade quilt raffle will raise additional funds. The event may be modest, but it underscores the district’s continued role as one of the community’s only civic anchors.

The following night, December 18, the board will hold its next meeting—the first opportunity for the public to learn whether Bonanza Peak Solar has responded to SIFPD’s request for substantial safety funding. That meeting will begin to clarify whether the district and the developer are moving toward negotiation as the project edges closer to permitting.

Whether SIFPD scales fast enough will determine not only how Charleston View absorbs one of the largest industrial projects in Inyo County history, but whether SIFPD can continue to protect its residents during an era of rapid change.

Leave a Reply