In The Nature Way: Wisdom from a Western Shoshone Elder, Corbin Harney—spiritual leader, activist, and member of the Western Shoshone Nation—shares a lifetime of teachings rooted in respect for the earth and all living beings. Drawing from oral traditions and his experiences confronting nuclear testing and environmental destruction in the Great Basin, Harney articulates a worldview that emphasizes balance, humility, and interdependence.

In his 2010 review for the American Indian Culture and Research Journal, historian David Rich Lewis explores the depth and significance of Harney’s message, situating it within the broader context of Native environmental philosophy and resistance to colonial exploitation. Lewis highlights how Harney’s voice bridges traditional ecological knowledge and contemporary environmental activism, offering both a cultural record and a call to conscience for readers navigating the modern world’s ecological crises.

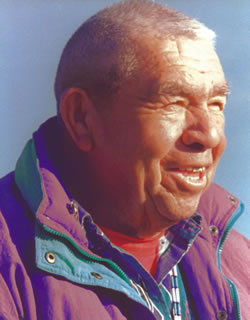

Corbin Harney (Dabashee) was born in 1920 to a Western Shoshone family living near Bruneau in southeastern Idaho. Raised by his grandparents and later by extended family members among the Duck Valley Shoshones of Nevada, Harney’s life illuminates the endurance of Native peoples making their way in a rapidly changing world. As a child he learned about the natural world from his grandmother and applied those traditional lessons in later life as he became aware of his calling as a spiritual healer. Harney went on to become an internationally recognized leader in the antinuclear movement and founder of the Shundahai Network, all while operating Poohabah, a traditional healing center in Tecopa, California, until his death in 2007.

The Nature Way is Harney’s posthumous treatise on the land wisdom and spiritual knowledge of the Newe, the Western Shoshone people. Harney’s narrative was recorded as a series of interviews conducted during several months in 2000 by Alex Purbrick, Harney’s media manager and secretary, while the two traveled across the Great Basin visiting Shoshone sacred sites, camps, and mineral springs. According to Purbrick, Harney envisioned this book as a whole and had a clear sense of what he wanted to say. “I rarely had to ask him any questions or remind him of places we had been,” writes Purbrick. “I simply pressed Play on the tape recorder and listened to Corbin’s voice until the tape ran out.” In the years that followed, Purbrick transcribed the tapes and then “rearranged everything into sections so that his thoughts would flow in an orderly sequence.” She edited sentences for clarity but tried “to keep the essence of his stories” intact, with “most accounts being word for word as they were recorded” (xii). Purbrick shared her draft manuscript with Harney who expressed his satisfaction even as he added comments and marginal notes for later elaboration. But the manuscript was unusual in its structure and voice, and languished for want of a publisher until shortly before Harney’s death when the University of Nevada Press picked it up.

Purbrick incorporated Harney’s final comments and added additional explanatory endnotes to clarify recent events and organizations mentioned in passing. The final product is Purbrick’s attempt to capture and structure a kind of timeless oral narrative, a Western Shoshone explanation for and view of traditional life and spirituality mediated through Harney’s experiences as a modern healer and antinuclear activist.

The meaning of the book’s title unfolds slowly. Harney offers fleeting glimpses of what makes up his larger metaphysical system of the Nature Way through a series of lessons built one upon another across the book’s four sections. Harney begins by recounting his childhood and later activism. He describes growing up Shoshone and poor in the 1920s, the spiritual lessons he learned from his grandmother and uncle, his flight from boarding school, his years of wage labor and travel across the Great Basin, and then his activism on behalf of Shoshone treaty rights beginning in the 1940s and against nuclear testing after 1985. This autobiographical section is rich in significance—not only of his life but also of the experiences of other Western Shoshones.

Unfortunately, it is spare in details and leaves much unspoken. The second section comprises Harney’s recitation of the historical mistreatment of the Newe and his descriptions of Shoshone sacred places and resource campsites and how government and nuclear testing have damaged them. The sense of persecution and injustice is palpable in his litany of generic and specific charges against whites and state and federal governments. Some are amalgams of traditional stories and postcontact events (for example, cannibalism and forced Shoshone removals to Canada, 33–34) repeated orally over time to connect past and present, generating a sense of group identity and purpose. Other charges are all too genuine and familiar: pervasive racial discrimination and economic marginalization, the abrogation of treaty rights, and the desecration of Shoshone burials.

Purbrick reveals the heart of Harney’s concerns in the book’s third section, “Newe Wisdom.” Here Harney describes the healing powers of prayers and songs and provides a Shoshone pharmacopeia of plants, roots, berries, and their medicinal properties. He attaches stories of both cultural and personal significance to each of these songs and plants, illustrating the continuity between myth-time and present and how essential spirits inhabit all things. This is ethnologically rich material, Shoshone traditions and cosmologies interpreted by a modern practitioner. Building from this background knowledge, we reach Harney’s most sustained explication of the Nature Way concept.

According to Harney, all life (animate or inanimate) has a spirit, voice, and song, and each is responsible for caring for and working with each other, for asking and offering each other help. Everything was put here for a reason, each in its place, and everything has the power to heal or give strength. Humans need to recognize the spirit and power in all things Mother Earth has given us by listening to the songs of each and, in turn, singing back to nature in order to show our appreciation. Unfortunately, according to Harney, we are ruining the world and ignoring that reciprocal relationship. We must change, for without the healing powers of nature we won’t survive. We need to understand where our medicine comes from before we lose it altogether, then sing our songs of appreciation and pass on that traditional knowledge to another generation.

In essence, this was Harney’s intent for the book—to explain and pass along an awareness of what spiritual power is, how it manifests itself, and how it should be treated. Throughout The Nature Way, Harney reiterates that nature chooses individuals (human or otherwise) to doctor their own kind and each other, but that each has to be able to hear that calling and discover their songs and the power to heal, and that each has to be asked and then thanked for their help. Healing isn’t just about personal health but about social and environmental health as well. In the end, Harney’s message is about healing nature, particularly from the catastrophic impacts of nuclear weapons testing and nuclear power generation and waste disposal. Harney’s observations on these issues comprise the final section of this book, just as they served as foci for his efforts as healer and spiritual leader in later life.

It is easy to see The Nature Way as a spiritual and cultural guidebook, transmitted autobiographically in the tradition of older narratives by and about elders and spiritual leaders such as Nicholas Black Elk, Maria Chona, Thomas Yellowtail, Pretty-shield, or John Lame Deer. Harney’s narrative is shorter and more limited than these, but it shares the same “as told to” feeling and organization, albeit with a modern activist sensibility and self-consciousness, or sometimes a lack thereof. It’s less about him specifically than about his desire to raise awareness of pressing issues. What makes this narrative particularly worthwhile are its Western Shoshone and Great Basin focus, ethnological contributions, and very personal metaphysical formulation of a larger universe of Native belief and behavior that (in a pan-Indian sense) transcends place, group, or time. It joins a growing number of Native meditations on the health of the environment as an indicator of our collective spiritual state and the tyranny of an industrial colonial culture. Its answers are as spare and enduring as Harney’s beloved Great Basin landscape, and as simple as his quiet but persistent message—we’re all in this together; we are bound in nature’s way; we need to listen and work together as one.

David Rich Lewis

Utah State University

“Water Song From the Morning Prayer,” performed by Harney on the album Tribal Waters: Music From Native Americans, is both a song and a ceremony. Sung in the Shoshone language, it honors water as a sacred, living presence—essential not only to survival but to spiritual balance. The song reflects Harney’s lifelong message, echoed in his book The Nature Way, that all life is interconnected and that protecting water is a moral duty. Through rhythm, chant, and prayer, Harney invites listeners to recognize the spirit within nature and to remember that caring for the earth begins with gratitude at dawn.

Sources:

Lewis, D. R. (2010). The Nature Way: Wisdom from a Western Shoshone Elder. By Corbin Harney. American Indian Culture and Research Journal , 34(1).

The Nature Way: Wisdom from a Western Shoshone Elder. By Corbin Harney,

as told to and edited by Alex Purbrick with a foreword by Tom Goldtooth.

Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2009. 136 pages. $18.95 paper.

For more information, visit the eScholarship repository from the University of California.

Leave a Reply